Henry VIII

(28 June 1491 – 28 January 1547)

Was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is best known for his six marriages, and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. His disagreement with Pope Clement VII about such an annulment led Henry to initiate the English Reformation, separating the Church of England from papal authority. He appointed himself Supreme Head of the Church of England and dissolved convents and monasteries, for which he was excommunicated by the pope.

Henry VII renewed his efforts to seal a marital alliance between England and Spain, by offering his son Henry in marriage to the widowed Catherine. Henry VII and Catherine’s mother Queen Isabella were both keen on the idea, which had arisen very shortly after Arthur’s death. On 23 June 1503, a treaty was signed for their marriage, and they were betrothed two days later. A papal dispensation was only needed for the “impediment of public honesty” if the marriage had not been consummated as Catherine and her duenna claimed, but Henry VII and the Spanish ambassador set out instead to obtain a dispensation for “affinity”, which took account of the possibility of consummation. Cohabitation was not possible because Henry was too young. Isabella’s death in 1504, and the ensuing problems of succession in Castile, complicated matters.

Name: Marital Status Children who survived

Catherine of Aragon – Divorced 1533 – Queen Mary 1

Anne Boleyn – Executed 1536 – Queen Elizabeth 1

Jane Seymour – Died 1537 – King Edward VI

Anne of Cleves – Married & Divorced 1540

Catherine Howard – Executed 1542

Katheryn Parr – Died 1548

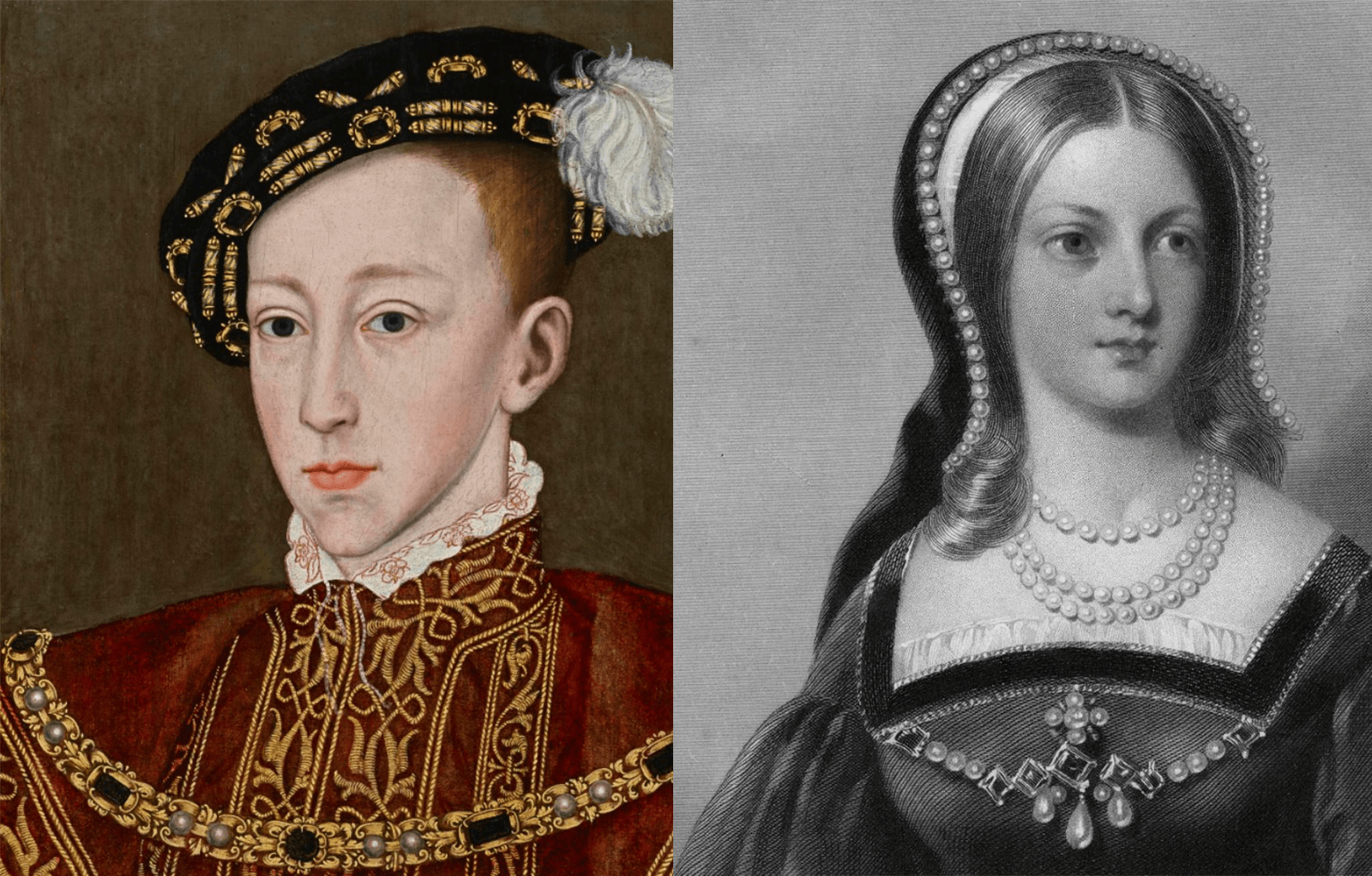

Edward VI

(12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553)

Was King of England and Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553.

He was crowned in 1547 at the age of nine. Edward was the first English monarch to be raised as a Protestant. During his reign, the realm was governed by a regency council because Edward never reached maturity. Edward named his Protestant first cousin once removed, Lady Jane Grey, as his heir, excluding his half-sisters, Mary and Elizabeth.

Lady Jane Grey, (born October 1537, Bradgate, Leicestershire, England—died February 12, 1554, London)

Titular queen of England for nine days in 1553. Beautiful and intelligent, she reluctantly allowed herself at age 15 to be put on the throne by unscrupulous politicians; her subsequent execution by Mary Tudor aroused universal sympathy.

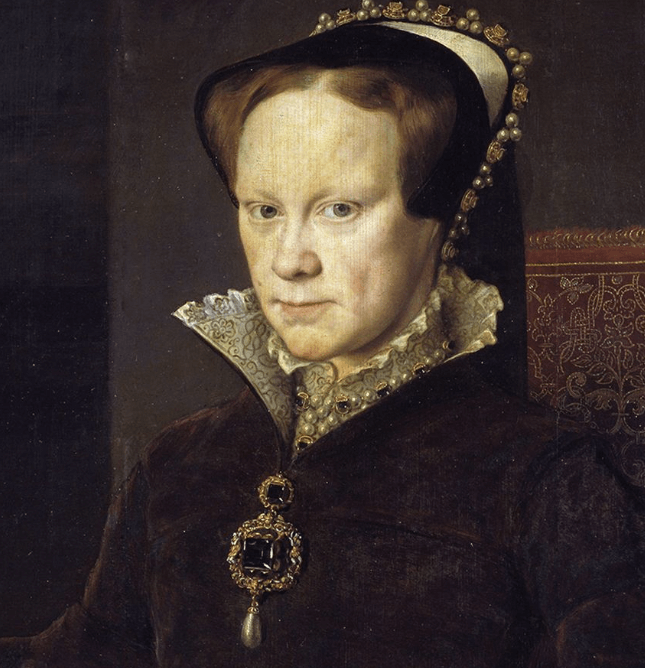

Mary I

(1516-1558)

Took the throne in 1553, reigning as the first queen regnant of England and Ireland. Seeking to return England to the Catholic Church, she persecuted hundreds of Protestants and earned the moniker “Bloody Mary.” Mary married King Philip I of Spain and they became “by the grace of God, King and Queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, and Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabant, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol” However she never left England and Philip held the position of King for Mary’s lifetime only.

Philip II

(21 May 1527 – 13 September 1598)

Deeply devout, Philip saw himself as the defender of Catholic Europe against the Ottoman Empire and the Protestant Reformation. In a political move, he married Mary and became King of England and later Ireland but only for Mary’s lifetime. However, Mary did not produce an heir and Elizabeth I became Queen of England.

Upon Mary’s death, the throne went to Elizabeth I. Philip had no wish to sever his tie with England, and had sent a proposal of marriage to Elizabeth, he did not get a reply. He continued to support England in European politics until Elizabeth allied England with the Protestant rebels in the Netherlands. Further, English ships began a policy of piracy against Spanish trade and threatened to plunder the great Spanish treasure ships coming from the New World.

The execution of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1587 ended Philip’s hopes of placing a Catholic on the English throne. He turned instead to more direct plans to invade England and return the country to Catholicism. In 1588, he sent a fleet, the Spanish Armada, to rendezvous with the Duke of Parma’s army and convey it across the English Channel.

Elizabeth I

(7 September 1533 – 24 March 1603)

was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last monarch of the House of Tudor and is sometimes referred to as the “Virgin Queen“.

Francis Drake had undertaken a major voyage against Spanish ports and ships in the Caribbean in 1585 and 1586. In 1587 he made a successful raid on Cádiz, destroying the Spanish fleet of war ships intended for the Enterprise of England, as Philip II had decided to take the war to England.]

On 12 July 1588, the Spanish Armada, a great fleet of ships, set sail for the channel, planning to ferry a Spanish invasion force under the Duke of Parma to the coast of southeast England from the Netherlands. The armada was defeated by a combination of miscalculation,[l] misfortune, and an attack of English fire ships off Gravelines at midnight on 28–29 July (7–8 August New Style), which dispersed the Spanish ships to the northeast. The Armada straggled home to Spain in shattered remnants, after disastrous losses on the coast of Ireland (after some ships including La Girona had tried to struggle back to Spain via the North Sea, and then back south past the west coast of Ireland).

Unaware of the Armada’s fate, English militias mustered to defend the country under the Earl of Leicester’s command. Leicester invited Elizabeth to inspect her troops at Tilbury in Essex on 8 August. Wearing a silver breastplate over a white velvet dress, she addressed them in one of her most famous speeches:

My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourself to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people … I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince of Europe should dare to invade the borders of my realm.

Portrait commemorating the defeat of the Spanish Armada, depicted in the background. Elizabeth’s hand rests on the globe, symbolising her international power. One of three known versions of the “Armada Portrait”. (see image)

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced. Elizabeth’s procession to a thanksgiving service at St Paul’s Cathedral rivalled that of her coronation as a spectacle. The defeat of the armada was a potent propaganda victory, both for Elizabeth and for Protestant England. The English took their delivery as a symbol of God’s favour and of the nation’s inviolability under a virgin queen. However, the victory was not a turning point in the war, which continued and often favoured Spain. The Spanish still controlled the southern provinces of the Netherlands, and the threat of invasion remained.

Phone

+44 (0) 7486 290430

VISIT

8am to 5pm

Mont–Fri

sec.portballintraeheritage@gmail.com

Address

81 Beach Road, Portballintrae, Bushmills, Northern Ireland